Chart 1: Canada’s export concentration stands out globally

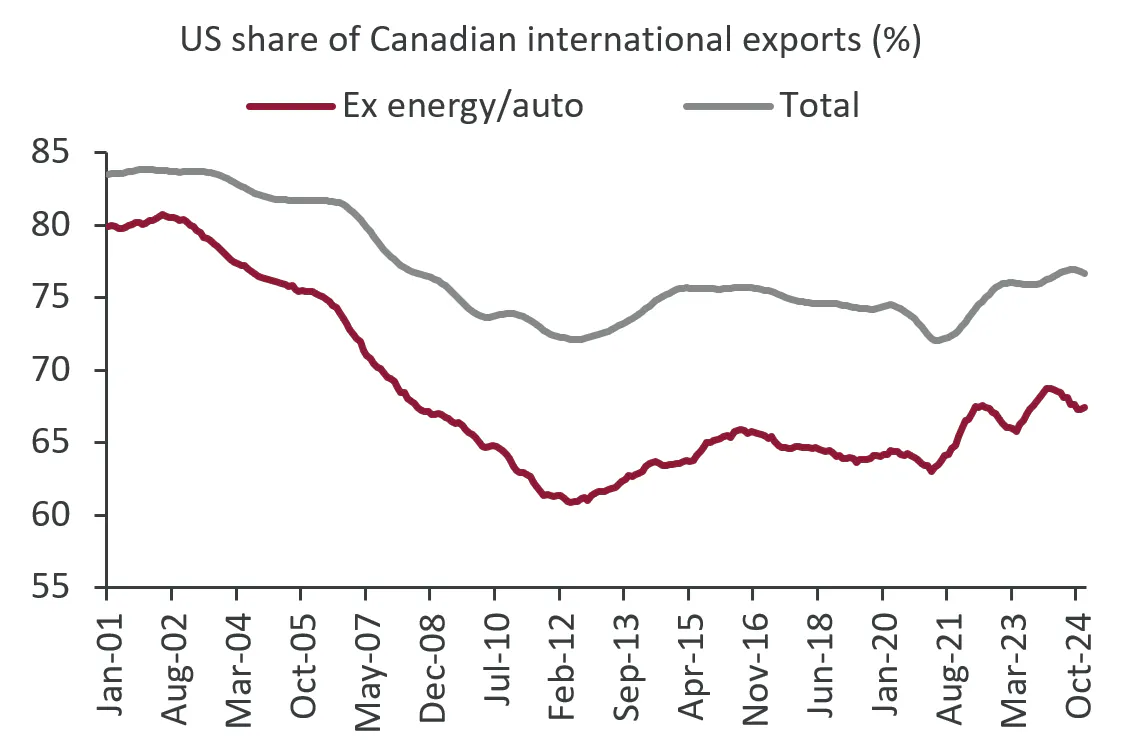

Canada’s export dependency with the US isn’t just mathematically high, at roughly 75% it stands out as one of the most geographically concentrated export bases globally (Chart 1). Recent tariff threats have correctly brought this to attention and hastened calls for action to diversify. However, diversifying exports away from the US will firstly require a reversal of the recent trend which has seen more trade flow south of the border, and the reestablishment of trade links with customers in other countries and provinces. History shows that greater diversification can be achieved, but results will not be seen overnight.

Reversing the trend

Canada’s large trade dependency with the US partly reflects a high level of concentration in two key areas – energy and autos. For energy exports this dependency will be maintained unless new oil pipelines flowing east are approved and laid. While recent tariff threats from the US appear to have improved enthusiasm for such pipelines, if there is progress it will take a number of years to come to fruition.

For autos, the high dependency reflects the intertwined nature of the North American auto industry more generally, as cars and parts cross borders at different stages of construction. This means that the contribution of autos to GDP appears much larger when judged by a share of exports (3% of GDP) than production (less than 1%). This doesn’t mean that the auto sector is not important, far from it. However, it’s inclusion within the overall export picture does bias upwards Canada’s overall trade dependency with the US.

When it comes to recent export trends, though, trade in autos or energy isn’t the main concern. What’s more worrying is that excluding those two areas of high dependency, the proportion of exports destined for countries other than the US has declined steadily over the past decade. Excluding autos and energy, export concentration to the US reached a low of 60% just over a decade ago, but that proportion has been climbing steadily since (Chart 2).

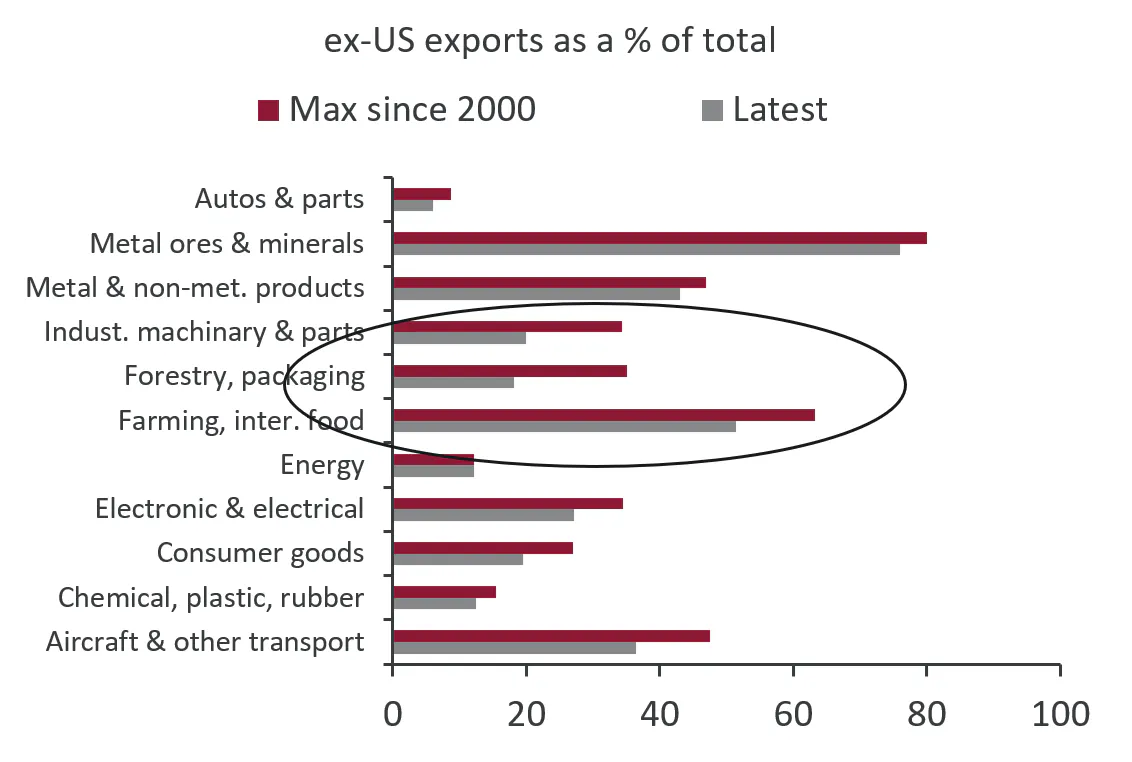

Certain industries that had previously made strong inroads to diversify have had much less success recently. Forestry, building packaging materials, as well as industrial machinery and parts, had seen ex-US exports approach 40% of the total at their peak. Now, they are back below 20% again (Chart 3). Almost two thirds of farming & intermediate foods exports had been sent to countries other than the US at their peak, but now that proportion is down to roughly 50%.

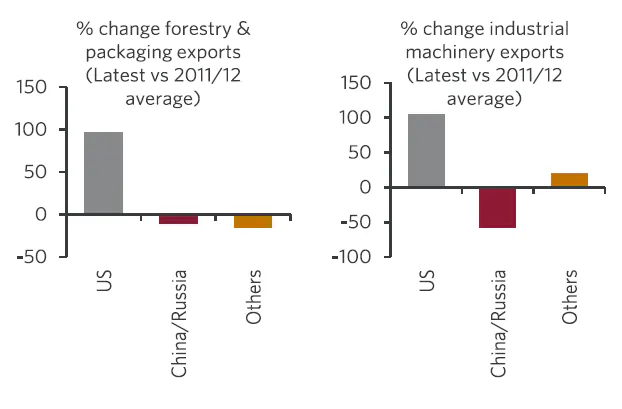

This worrying trend partly reflects a change in the global political landscape, and in particular frostier trade relations with China and sanctions placed on Russia. However, looking in detail at exports of forestry & packaging products and industrial machinery shows that these two countries can’t fully explain the backstep Canadian exporters have made when it comes to ex-US trade. In the case of the former, exports to other countries (ex US, China and Russia) have also fallen, while for industrial machinery the growth in exports to such nations was tiny compared to the surge seen in US trade (Chart 4).

Of course the greater proportion of trade destined for the US today, compared with a decade ago, could partly reflect the fact that the American economy has outperformed other developed economies. That growth in demand, combined with the obvious geographical advantage, has enabled companies that export to the US to scale up those deliveries.

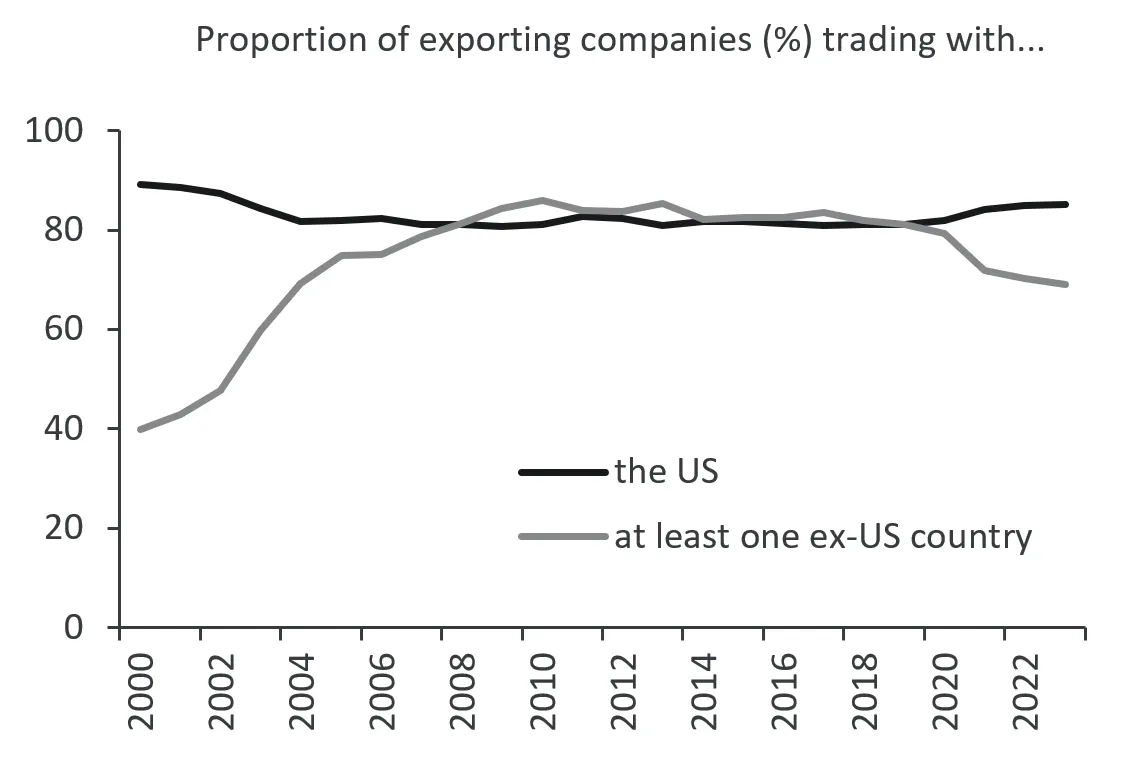

However, this doesn’t appear to be the only reason, and another contributing factors appears to be a decline in the number of trade links Canadian exporters have with other countries. Examining data on the proportion of companies who export (rather than the value of the goods themselves) shows that between 2006 and 2020 roughly 85% of exporters sent goods to the US and approximately the same proportion had links to at least one other country (Chart 5). Unfortunately, the proportion trading with at least one other country has fallen below 70% recently. The number of companies exporting to both Asia and Europe is at the lowest in more than 20 years (Chart 6). So for some companies diversifying will require establishing new trade links, rather than just trying to scale up existing ones.

A time for self-reflection

Reducing the dependance of Canadian exports on US demand doesn’t just mean diversifying to other countries. It can also mean trying to improve interprovincial trade flows. While that’s a laudable goal, our upcoming research will show that reducing interprovincial barriers might not be quite as large a boost to overall GDP as others have suggested.

True, back in the early 1980’s interprovincial trade and international trade were roughly equal as a proportion of GDP. However, while exports to other countries has risen as a share of the economy, trade between provinces has fallen by a similar amount (Chart 7). But some of that shift reflects the role of imports, including those from China and other emerging markets, in supplanting Canadian production in consumer goods like clothing, and the rising share of Canadian goods sector activity in industrial sectors like energy where trade is oriented north-south. Without a major reorientation, the composition of our current industrial mix may now be less amenable to an expanded role for east-west trade within the country.

Seeking diversification

The need to diversify and become less reliant on US demand is obvious, but doing so will be difficult. Some companies cannot just try to scale up exports to other countries, but rather need to establish/reestablish relationships in other countries. Increased interprovincial trade could play some role in reducing our dependance on US demand, but the scale of such opportunities is likely constrained by both geographic realities and our industrial mix. The good news is that, particularly on an individual sector basis, we have been able to achieve greater trade diversification before. We need to replicate that prior success across the economy more broadly.