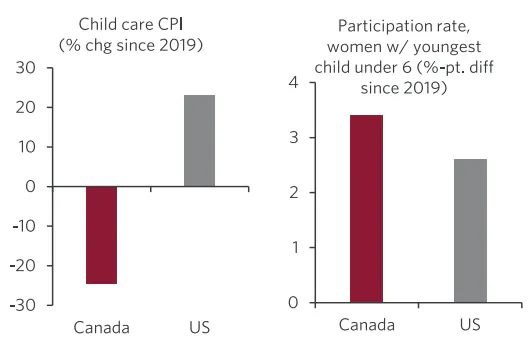

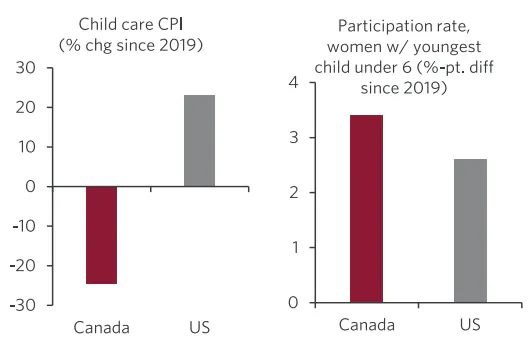

Chart 1: Sharp drop in child care costs in Canada due to subsidies (L), has helped women increase representation in the labour market (R)

Canadian women are amongst the most active in the labour market globally, but progress on another front, what women are paid for those positions, remains more sluggish. On that score, looking at educational attainment, and the ability of women with young children to stay active in the labour market, there are some trends in Canada that could support a further narrowing in the gender pay gap ahead, but other factors where more progress will be necessary.

Women in the workforce: Canada’s cup is more than half full

Within the G7, Canada is only a tick below Germany’s lead, with a female participation rate of 76.4% for the 15-64 age group. So the cup is more than half full, but there’s still a gap relative to male participation in Canada, and relative to some other countries that top the chart.

Canada is in 13th place among OECD countries, with the top three countries being Iceland, Sweden, and the Netherlands that have 82-85% of working age women in their labour markets. One thing these leaders have in common is accessible child care, an encouraging sign for Canada’s female labour force participation ahead, given this country’s increased efforts to extend greater access to affordable daycare.

The impact of subsidized daycare is clear when comparing developments across the Canada-US border. The federal government’s $10-a-day daycare mandate and the active engagement of provincial governments has seen childcare costs drop in Canada by roughly 25% since 2019, in a period in which US costs have climbed by more than 20% (Chart 1, left). That has supported a larger climb in the participation rate of Canadian women with young children (Chart 1, right). And not all provinces have seen a full reduction in childcare costs yet, which suggests further gains in participation are likely to happen in the future.

Looking further back, Canada’s greater progress in female labour force participation was already in place in earlier decades (Chart 2). Quebec’s generous childcare program, as well as the establishment of junior kindergarten, were among the drivers of that outperformance, one reason why the Canada-US differential has been even wider when looking at women with children under six.

Canada and US see sluggish progress on the gender wage-gap

By allowing women whose pay rates might otherwise be too low to cover childcare costs to enter the workforce, affordable daycare programs can act, at least initially, to increase the measured pay gap between men and women. But it will help to close it in the long-term as women with children won’t lose as many years of experience when their children are young, and have a better chance at breaking the glass ceiling as a result.

Canada’s wage gap is indeed on the higher end of the range across countries (Chart 3). But pulling lower-wage women into the workforce through childcare subsidies doesn’t appear to be the key part of that story, at least when looking at the relationship between labour force participation rates and the wage gap across OECD countries, where there is no discernable correlation. Wage gaps in Iceland and Sweden are low despite having the highest participation rates for women. And Canada’s wage gap isn’t materially smaller than that of the US, despite a wide gap in participation that favours Canada.

In research we published last year, we found that the narrowing in Canada’s gender wage gap had slowed dramatically in recent years, but that seems to be a trend shared by America’s labour market (Chart 4, left), judging from the median earnings of full-time workers. Note that the declining share of relatively-high paying jobs in sectors like manufacturing, and the resulting exit of men from the US labour force, is making its wage gap look smaller relative to Canada (Chart 4, right), where male participation hasn’t seen the same degree of erosion.

What’s behind the pay gap and progress ahead

Gender wage gaps aren’t necessarily a product of discriminatory pay practices. They capture not only wage differences between workers in the same position, but also divergences in the types of occupations in which men and women are employed, and their progress through the ranks over their careers.

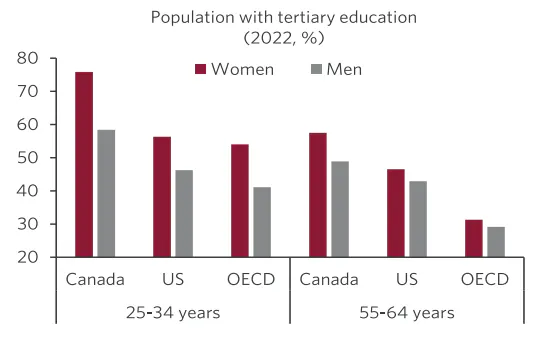

Educational attainment, at least in terms of years of schooling, should be driving progress towards narrower gender wage gaps. Globally, women are more likely than men to have post-secondary education, and that’s true in Canada to a much higher degree (Chart 5). That should be associated with higher productivity and therefore pay increases in the labour market. It’s possible that some of that impact still lies ahead, as younger women are more educated than those in their later years in the workforce. As older workers retire out of the workforce, and younger women move up the ranks, we should expect to see some narrowing of the wage gap.

But what fields of study are pursued by men and women can also be important for wage gaps. There are notably divergent returns to years of study across the hard sciences, business, social sciences, and humanities.

In maths and sciences, of increasing importance given the economy’s technology tilt and the role of math in fields like finance, women still appear to be disadvantaged by the way these disciplines are taught, and the combination of social and other forces that impact choices over fields of study. Encouragingly, there are no statistically-significant gaps in boys’ and girls’ PISA science test scores in Canada at the grade 10 level. But in math, girls’ median scores still trail those of boys, and there’s a larger gap at the top end of the scale, in the average score of boys in the top 10% versus girls in the top 10% of their cohort (Chart 6, left), although to a somewhat lesser degree than what we see in US scores. Both countries show wider gender disparities than the OECD average.

What’s concerning, is that if we look at all of those in the overall top-quintile of STEM test scores as of grade 10, a smaller share of women who are high achievers will go on to enroll in STEM fields at the bachelor’s degree level (Chart 6, right). The result is that while Canadian women account for 59% of undergraduate degrees conferred, their representation isn’t as strong in business and STEM degrees (science, technology, engineering, and math), at 53% and 40%, respectively.

More women in leadership roles needed

It’s not just career choices, but progress towards the top positions within each field that can drive pay differentials. Here, Canada has some work to do if women are to narrow the pay gap ahead. At the top end of the income spectrum, the pay gap has widened notably in recent years in Canada (Chart 7, left), as pay increases to top income earners have outpaced average earnings growth, and those jobs are still skewed towards men. We identified some of these occupations in last year’s International Women’s Day paper, and we now find that development to be at odds with what other countries are seeing.

Both the US and the OECD have seen the glass ceiling become less prominent since the mid-2000s, with the pay gap in the 9th decile narrowing (Chart 7, right). That lack of progress in Canada partly explains the underperformance in closing the pay gap despite having a high participation rate for women. In line with that, there hasn’t been any progress in terms of women’s share in managerial positions since 2013, while other countries have seen gains (Chart 8).

The road ahead

As we celebrate International Women’s Day in 2025, we can look back with some pride at the growing role of women in the workforce in recent decades, not only in Canada but also globally. On the wage front, progress appears to have slowed in narrowing gender wage gaps, but some of the underpinnings for momentum in that direction appear to be in place in Canada. Affordable and available childcare are encouraging more women with young children to remain in the workforce, and prior research has shown that reducing the number of years spent out of the workforce should work to narrow wage gaps later in women’s careers. Women are also garnering more years of educational attainment than men, and that’s particularly evident for younger women who will over time replace older women with fewer years of study.

But we also note that social and other forces are still resulting in occupational and educational choices that could impact pay rates for women less favourably, and progress towards an increasing share of women in managerial positions also appears to have stalled in Canada, while advancing elsewhere. A better understanding of the forces behind these trends could be important in identifying what needs to be done to ensure that women are not only in the workforce, but that the economy is making full use of their talents.