Chart 1: Steady decline in manufacturing as a share of GDP and employment

This year’s trade war goes beyond manufacturing, with tariffs levied on agriculture, mining and forestry products, but at its heart is a White House desire to see factory jobs return to America’s shores. A two-way trade war might not actually generate that result, since it can jeopardize jobs tied to factory exports due to retaliatory tariffs abroad, and raise costs for manufacturers that use imported inputs. But more fundamentally, we should be asking whether regaining factory jobs is in itself a worthwhile goal, given that the US economy entered this year at close to full employment.

There’s no doubt that in output or employment, the US factory sector no longer pulls as much weight in the nation’s overall GDP. As has been the case in other advanced economies, manufacturing has given way to services in terms of its share of economic activity, and even more so, in its share of employment (Chart 1). The job count decline reflects the strong labour productivity gains seen in the decades prior to 2010 that were tied to automation. To some extent, it also captures the fact that what were once counted as employment by manufacturers now shows up as jobs at services companies that have been contracted to supply cleaning, security and other functions at America’s factories.

But remember that the US entered 2025 essentially at full employment. So we’re not talking about increasing total employment or absorbing an overhang of Americans looking for work. Gains in manufacturing jobs, and particularly, in the kind of manufacturing jobs that have now been supplanted by imported goods, would have to entail reallocating workers from other sectors. The evidence suggests that such a reallocation would not, in fact, represent a clear improvement in American living standards.

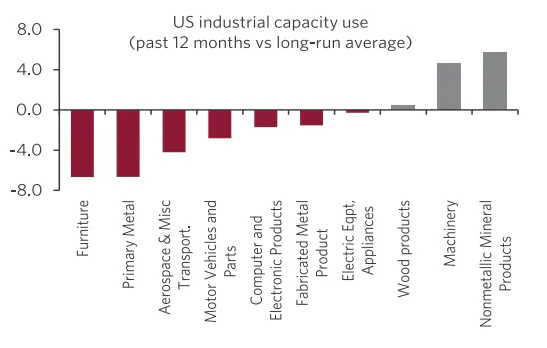

In the near term, the ability to squeeze out imports will vary based on the capacity of existing facilities and the availability of labour. In terms of the former, capacity use figures, while sometimes including capacity that isn’t really functional, does suggest that there’s some room at the inn in sectors where the US has applied higher-than-average tariffs, including primary metals (steel/aluminum) and motor vehicles. Both of those sectors, along with aerospace and furniture, have been operating at capacity use rates that are below their longer term norms (Chart 2).

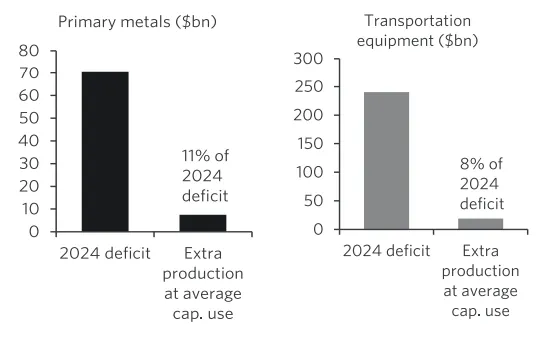

Even so, restoring them to their typical capacity use rates wouldn’t do much to dent America’s trade deficits in metals or transportation equipment (Chart 3). Bringing those sectors into a balance of trade with the rest of the world would require major additions to current capacity, which would typically be a multi-year process. In the near term, then, imports would continue to have a major slice of the US market, and American buyers of these products would face higher costs.

Labor would be the greater challenge, and it’s not clear that shifting workers from where they are currently employed, into the kind of manufacturing jobs that would be needed to substitute for imports, would represent a gain. There’s a tendency to romanticize the glory days of manufacturing employment from decades ago. But it’s worth remembering that meat packing plants, or rows of sewing machine operators making t-shirts, are also part of the manufacturing sector, and while they are welcome sources of employment for some, today’s younger workers are more likely to see their ideal employer elsewhere.

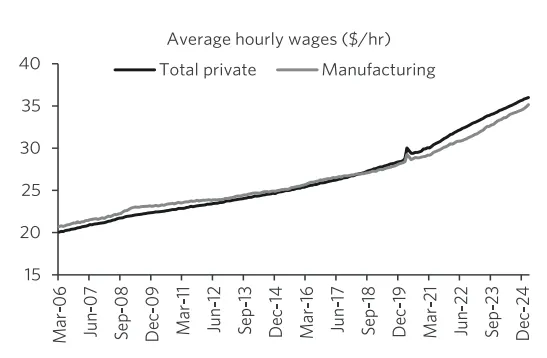

That’s also because the notion that factory jobs carry higher pay is also a historical anachronism. Average hourly wages in manufacturing stopped topping average private sector pay a decade ago, and that gap has been widening since the pandemic (Chart 4), despite the fact that robots replaced some of the lower paid positions on assembly lines.

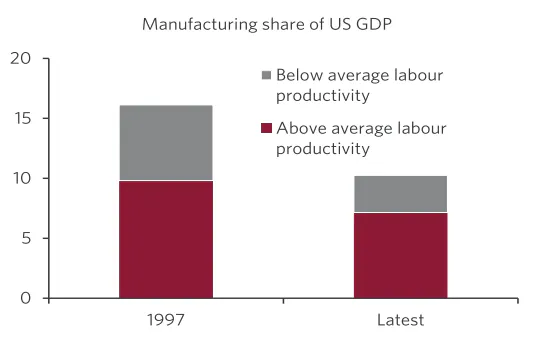

While manufacturing productivity was strong prior to 2010, which would usually be positive for wage inflation, the final selling prices of manufactured goods have come down, limiting wage growth in the sector. Indeed, it has been price movements relative to others in the economy that account for most of the decline in manufacturing as a share of nominal GDP (Chart 5). The volume of manufacturing production has risen at a similar pace to activity in the rest of the economy.

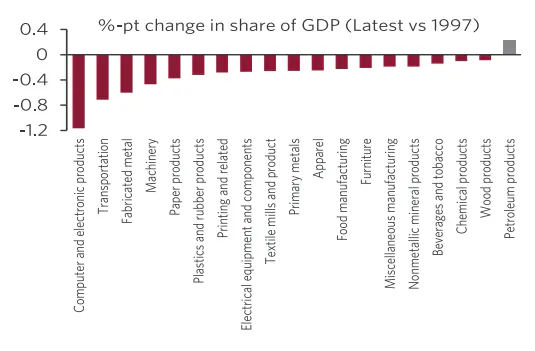

The decline in manufacturing jobs as a share of the labour force is therefore a reflection of increased productivity. This is happening within sectors, but also reflects the fact that the US industrial sector has become increasingly focused on higher productivity subsectors (Chart 6). Lower productivity subsectors that have lost a greater share within GDP are in the types of facilities where employees simply didn’t generate enough output per hour to justify American-style wage rates, and were shifted to emerging market economies with lower pay scales. Why put tariffs on foreign-made shoes, t-shirts, low-end toys and the like if making them in the US of A would put Americans to work in low-paid, low-productivity positions?

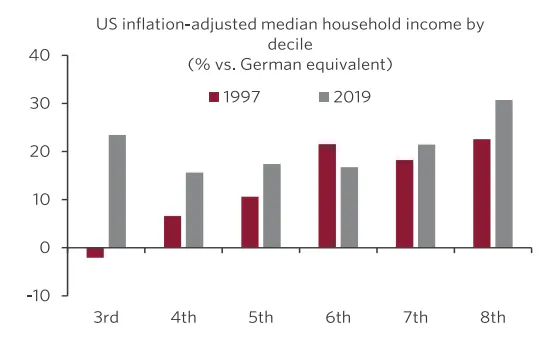

International evidence also suggests that there isn’t a tight relationship between the share of activity in manufacturing and living standards. True, moving from a rural, agrarian society to an urban, manufacturing economy is often an important step up the economic development ladder. But a knowledge-based services economy can often be a gain for a high-income economy these days. Back in 2019, Germany was still a manufacturing powerhouse, while the US had given up a lot of factory ground over the prior decade, yet across the income spectrum, Americans had widened their gap with German households in terms of real incomes (Chart 7).

However, a more detailed examination of where the manufacturing sector has lost share in recent years does highlight a few high-productivity areas where there has been a sharp decline (Chart 8). Perhaps unsurprisingly, these include areas such as metals and transportation that have already been targeted with sector-specific tariffs. The White House is also apparently musing sector-specific tariffs on electronics as well, which has seen the largest decline as a share of GDP but where jobs aren’t actually that elevated in terms of productivity.

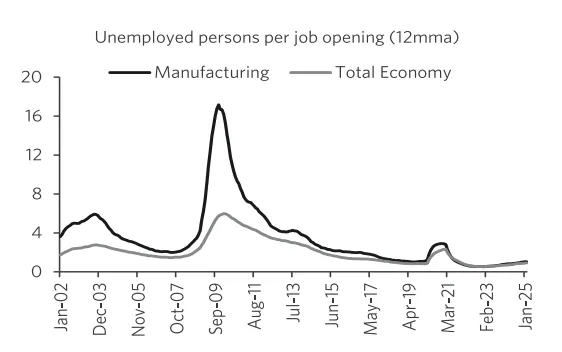

The other reality is that those who were employed in the larger American manufacturing workforce decades ago have retired or moved on to other positions, and it would be difficult to find those to replace them. Unlike where we were at the turn of the millennium, or even more so, during the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis recession, we don’t have an overhang of unemployed manufacturers waiting to take positions that become available. In both the factory sector and the overall economy, there are very few unemployed Americans relative to the number of open positions (Chart 9).

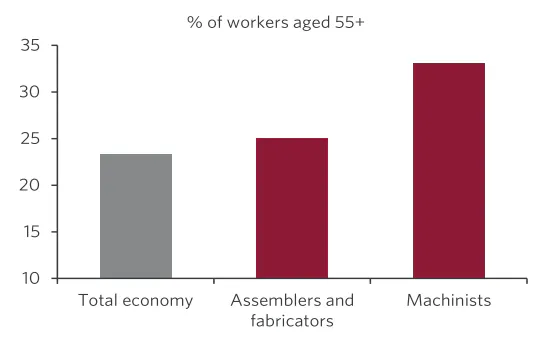

Tight immigration policies, education choices, and an aging population will only make expanding the factory sector an even greater challenge in the years ahead. Manufacturing workers tend to skew a few years older than the average worker across the economy, and a higher share of them are now over 55 (Chart 10). They are also sometimes in physically demanding roles that are tied to earlier retirement.

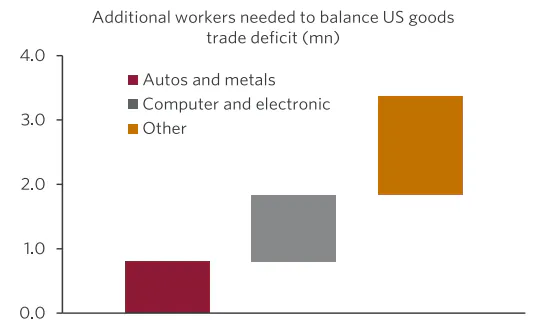

A lack of available workers will then be a big headwind to achieving a reshoring of manufacturing activity. In order for the US to achieve a balanced trade in goods, the extra domestic production needed would require an additional 3.3 million workers, which is equivalent to almost 2% of the current labour force (Chart 11). Obviously that can’t and won’t happen, but the calculation includes large increases in low productivity sectors which shouldn’t be the primary target of the US’s manufacturing ambitions.

However, even just balancing trade in autos, metals and electronics (those areas where the US has lost the most ground in recent decades and have had sector-specific tariffs either implemented or threatened) would require an additional 1.8 million workers, or roughly 1.1% of the current workforce. Just achieving that would be a tough ask with the labour market already at, or close to, full employment.

Moreover, in electronics, it’s about more than just the number of available workers, but about their training and skill sets. An leading CEO in that sector noted that China’s current edge in electronics isn’t just about wages, but about the vocational training and skill sets of its workers, with the US education system more tilted towards skills in digital design and services rather than tooling engineers. It would be a long road to either train a sufficient number of Americans, or bring in immigrants with these skills, along with the entire nexus of facilities needed to replicate what’s now present in Asia.

None of this is to say that there wouldn’t be grounds for narrowly based protectionist policies against a narrow list of trading partners. The US might have non-economic reasons to promote its semiconductor or defense equipment sectors, and there’s an argument that trade has been distorted in some cases by government subsidies in non-market economies. But those who pine away for the good old days when factory towns were more plentiful need to remind themselves that, in the period since then, American real incomes have risen, workers have moved on to other employment, and now face a labour market in which manufacturing jobs are no longer providing higher than average pay.

Tariffs might fail to bring back manufacturing jobs for a host of reasons, including restraints on US factory labour supply, retaliatory levies by America’s export targets and the impact of tariffs on intermediate goods on American factory cost-competitiveness. But even if they worked, and somehow didn’t also reduce living standards due to higher prices on imports or domestic substitutes, the goal itself might not represent the win that many believe.